“If you are interested in stories with happy endings, you would be better off reading some other book. In this book, not only is there no happy ending, there is no happy beginning and very few happy things in the middle. This is because not very many happy things happened in the lives of the three Baudelaire youngsters.”

If that isn’t a good summary for this series, I don’t know what is.

Hello, everyone. I hope that your holidays proved enjoyable (or, at the very least, something not-dreadful). Welcome to the new year! I hope that we all find plenty of good in the coming months, whether it be in a book, a movie, a song, or that ridiculous and decidedly unfun thing that we call ‘life.’

For my first contribution of 2017, I’ve decided to get somewhat ambitious. Today (finally) marks the release of Netflix’s new adaptation of Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, with a first season covering the first four books Snicket’s thirteen now available for your binging pleasure.

To commemorate the event, I have for you a combination summary and review of the series in its entirety. All thirteen of the primary books, along with two supplementary works: Lemony Snicket: The Unauthorized Autobiography and The Beatrice Letters. The only bits not covered this time around are the four installments in Snicket’s prequel series All the Wrong Questions. Since those are mostly related to the author’s past and not the Baudelaire’s various misadventures (though they do take place in the same universe and do shed light on some elements of it), their various parts and particulars aren’t necessary for understanding the series in either of its forms, so I’ll be saving that review (along with one for the eight new episodes of the show) for another day.

Now, with all of that out of the way, let’s talk about the Baudelaires, and why I love them.

Being an Account of the Trials and Triumphs of Violet, Klaus, and Sunny Baudelaire: A Story Told in Thirteen Parts

First off, know that I speak of these books very fondly and through the untrustworthy haze of childhood nostalgia. I remember ordering them in sets from Scholastic during our elementary school’s annual book fairs. It was a simpler time then. I got through most of the series (all the way up to the eleventh installment) before I left that grade range and moved on to junior high, which meant that I no longer had to wear uniforms (great!), but also had to deal with more puberty and decidedly fewer book fairs (not so great!). A disappointing trade, really.

As a result, it took me a few more years to finally get around to the last few books (though I never did get to finish my personal collection of paperbacks), by which point the hubbub surrounding the grand finale had died down (more on that in a bit) and we all had had the opportunity to move on to the edgier and much cooler books that had previously been off-limits. Harry Potter reached its end with The Deathly Hallows but was still going strong thanks to all of the film adaptations, Twilight suddenly consumed the world, and The Hunger Games came around not long afterward to pick up the hype and ensure that you weren’t ‘with it’ pop-culturally unless you had read the latest big thing in young-adult fiction.

And subsequently hated its ending, of course. Though I never had much of a problem with any of them, ‘Albus Severus’ and ‘the bravest man I ever knew’ aside.

(But, really. C’mon, Harry.)

Anyway, A Series of Unfortunate Events was buried under the resultant avalanche of copycat series that were hungry for a quick and easy cash-in via bookstore sell-outs and motion picture rights. And, really, it was pretty likely to come so long as you wrote about neglected children discovering magic, then angst-ridden teenagers being undead and attractive and willing to die for the sake of their unhealthy relationships, then future civilizations ruled by unlikely and gimmicky social structures that could be overthrown in three books by cool girls who didn’t play by the rules.

Sure, we got the Jim Carrey movie, but that only covered the first three novels and had its own issues.

(I will also defend it with my dying breath, but that is a conversation for another time.)

So. Thirteen books. To get things started, let’s look at a brief summary of them all, along with my scores for each:

Book the First

The Bad Beginning

★★★★☆

Siblings Violet, Klaus, and Sunny Baudelaire are sent to live with the devious Count Olaf after their beloved parents die in a fire that also destroys their home. Having to deal with the count’s volatile temper and unpleasant troupe of actors-come-henchman, the children must also foil their new guardian’s plot to steal the family fortune that Violet is due to inherit. Blanched string beans, the word ‘nuptial,’ a very boring play, and the semantics of the phrase ‘in one’s own hand’ are involved.

Book the Second

The Reptile Room

★★★★★

The Baudelaires are sent to live with their Uncle Monty: a kindly herpetologist with an enormous collection of creatures both deadly and docile and plans to take the children with him on his latest exploratory trip to Peru. The Baudelaires get to be happy for a whole fifteen pages before Monty gets a rather suspicious new assistant. Highlights include the unpleasant odor of horseradish, dramatic irony, zombies celebrating May Day, and a man drowning in a swamp while picking wildflowers.

Book the Third

The Wide Window

★★★★★

The Baudelaires are sent to Lake Lachrymose to live with their Aunt Josephine: a paranoid but well-intentioned woman who lives in an old house perched above the water. The Baudelaires are willing to make the best of the less-than-ideal situation, but are forced to take action when a familiar-looking ship captain arrives to woo Josephine. Be on the lookout for a medium-sized pile of tin cans, Cheer-Up Cheeseburgers, The Correct Spelling of Every English Word That Ever, Ever Existed, and the German word ‘wunderkind’ (which here means ‘someone who is able to quickly climb masts of boats being attacked by leeches’).

Book the Fourth

The Miserable Mill

★★★★☆

The Baudelaires are sent to live at the Lucky Smells Lumbermill in Paltryville with Sir, the owner. Forced to work long hours cutting wood with dangerous machines, things get worse when the nearby optometrist and her odd assistant prove less-than-trustworthy when repairing Klaus’s glasses. Also scattered throughout is a sign that says ‘beware’ in letters made out of dead monkeys, chewing gum, sensible beige shoes, and low self-esteem.

Book the Fifth

The Austere Academy

★★★★★

The Baudelaires have temporarily run out of individuals willing to care for them, so they are sent to Prufrock Preparatory to continue their educations at a boarding school. While the teachers are terrible and the classes are excruciatingly dull, the children manage to find some solace with their new friends and fellow students the Quagmires. Things are looking a bit brighter until the devious new physical education teacher arrives. Expect depressing triptychs, a half-hour violin sonata played twelve times in a row, Special Orphan Running Exercises, and stalks of celery.

Book the Sixth

The Ersatz Elevator

★★★★☆

The Baudelaires move into the city to live with family friend Jerome Squalor in his penthouse at 667 Dark Avenue. Though Jerome is decidedly kind, his wife Esmé is decidedly not, obsessed as she is with what is ‘in.’ Still, the situation is a good one until Esmé begins preparing for a fashionable auction with auctioneer Gunther, who isn’t quite so benevolent (or as trendy) as he appears to be. In the mix is the element of surprise, the King of Arizona, a pitch-black panther (covered in tar and eating black licorice at the very bottom of the deepest part of the Black Sea), and a doorknob made of the world’s second-finest crystal.

Book the Seventh

The Vile Village

★★★★★

The Baudelaires are adopted by the collective population of the Village of Fowl Devotees, as it ‘takes a village to raise a child.’ In the middle of nowhere and filled with crows, the orphans are expected to take on all of the chores of the town, but they at least find a refuge with handyman Hector, who lives amiably with the birds under the Nevermore Tree and tinkers on his own inventions in his spare time. Mysterious messages from the Quagmires and the appearance of a conniving gumshoe throw a wrench into things, however. Not to mention the complications brought about by a convention of orthodontists, a supermarket filled with vicious long-distance runners, mob psychology, and a huge cloud of dust that places no higher than twenty-fifth in a beauty pageant.

Book the Eighth

The Hostile Hospital

★★★★★

The Baudelaires, framed for a crime that they didn’t commit and left adrift, hitch a ride with a volunteer group hoping to spread some cheer among the patients of the nearby Heimlich Hospital. Hoping to learn more about the mysteries that have hounded them since their great loss, the children decide to volunteer in the hospital’s library of records, but face danger from not only suspicious staff who believe the Baudelaires to be murderers, but also the two-faced substitute superintendent and his posse of less-than-professional doctors, who are looking for the same information. Mixed up in the chaos are controversial vitamins, the Cathedral of the Alleged Virgin, the Ward for People with Nasty Rashes, and people with a severe lack of moral stamina.

Book the Ninth

The Carnivorous Carnival

★★★★☆

The Baudelaires are hitching rides again, and this time end up at the Caligari Carnival. A certain count hopes to consult with the fortune teller there to gain some answers to his own questions, and they’re ones that the orphans could also use, so they join the House of Freaks in disguise to stick around. No easy task, especially when also juggling buttermilk served in a paper carton, tagliatelle grande, ‘The Story of Queen Debbie and Her Boyfriend, Tony,’ and murder as a dramatic exercise.

Book the Tenth

The Slippery Slope

★★★★★

The Baudelaires are now the ones doing the pursuing as they follow their former guardian into the Mortmain Mountains. Hoping to at last untangle one of the mysteries most central to their plight(s) and prevent the Olaf from spreading any more destruction, the siblings seek to discover the location of a certain item of great importance before it can be snatched away by nefarious forces. Watch out for raw toast, a bookstore disguised as a café disguised as a sporting goods store, the central theme of Anna Karenina, and the final quatrain of the eleventh stanza of ‘The Garden of Proserpine’ by Algernon Charles Swinburne.

Book the Eleventh

The Grim Grotto

★★★★★

The Baudelaires are still searching for a certain item of great importance, and are now doing so underwater, aboard The Queequeg. Said object appears to have made its way into the Gorgonian Grotto, and it’s up to the siblings to brave the currents, fungi, and their old villain to search for it. Of course, a manatee accident, vicious and heavily-armed mountain goats, a woman disguised as a mailbox, and a tap-dancing ballerina fairy princess veterinarian are not helping matters.

Book the Twelfth

The Penultimate Peril

★★★★★

The Baudelaires are nearing the end of their journey, and now they’re in the midst of just about every friend and foe they’ve ever had the (dis)pleasure of meeting. Two groups — one benevolent, one decidedly less so — are converging on the Hotel Denouement, and something either very good or very bad is going to come out of this great meeting. It all comes down to who can find a certain item of great importance first, and the Baudelaires are the ones who can tip the scales in one party’s favor. Among all of the double-crossing and uncertainty is the Dewey Decimal System, a ball-playing cowboy superhero soldier pirate, unfathomable tones, and the legendary figure Giuseppe Verdi.

Book the Thirteenth

The End

★★★★☆

The Baudelaires and Olaf are left alone and adrift, with only their past failures and unanswered questions to keep them company as they confront one another for the final time. Things are explained, more are not, and our trio finally stops running. Come final twists, missed revelations, life lessons, and perhaps a death or two, it all comes to an end.

Still with me? Great! Thanks for sticking around. Despite its length, the series is a fairly quick read altogether, as none of the books are more than a few hundred pages. As such (and because none of us have the patience to write and/or read thirteen individual reviews all at once), I’m going to focus on them more broadly, particularly on how they work as a complete narrative. Since nobody is going to have to sink much time into scaling the papery heights of any one installment, they’re easy to binge, and so tend to blur together, anyway.

And because grouping the books into bunches seems to be popular (three for the original novels in their boxed sets, four for the television adaptation, et cetera), let’s follow suite. We’ll look at how the series develops, then summarize its overall merits to get a final score. The adventures of the Baudelaires do evolve in some noticeable ways when you section them up accordingly (and use fun titles), so let’s get to it:

Books 1-4

The Trouble Begins

Unsurprisingly, the first novels are arguably the weakest of the collection. Focused more on succinct, standalone plots, the initial three suffer mostly from being very repetitive. Each follows the exact same structure: the Baudelaires are introduced to their new guardian, the children learn to accept their new lives and begin to feel optimistic about the situation, then Olaf (outright in the first instance, in some sort of disguise in the second, third, and fourth) comes along and ruins everything. The Baudelaires warn whichever semi-trustworthy adult is in their periphery at the time, get ignored, and are forced to deal with the count themselves. Ultimately, they foil his plot to steal their family fortune, Olaf is almost captured before making a quick getaway, and the orphans are carted off to the next family member/friend/distant acquaintance is due to take them on. Fin.

Predictable and repetitive? Sure. Fun? Absolutely. Snicket is a clever enough writer to make the formulaic structure fairly easy to look past, and because you can burn through the initial four in a day or two, it isn’t as much of an issue as it might have been with a more time-consuming format. It’s something of a macabre vaudeville act: the comedy rule of threes — er, fours — being applied to the misfortune of children (ha ha) and the complete inability of grown men and women to recognize the very obvious danger that their charges are in. And then they usually die because of it (ha ha). It’s a joke of repetition: how long can the writer stretch the same premise until it stops being funny?

The answer here is ‘about three, maybe four, books.’ Which is good, because after The Miserable Mill, Snicket has about pushed the limits of his format, and you start wishing that he would change things up a bit. The fourth book manages to tweak things slightly — the Baudelaires find themselves in a setting other than somebody else’s strange house, and their new guardian is less involved in the storyline than the other periphery characters are — and strikes me as somewhat darker (mind control and sawblades being prominent plot points and all, though I suppose the others aren’t much cheerier) than the first three, but isn’t all that unique once you look past the minor details. It’s really just another episodic installment that doesn’t appear to push the characters or their situation in any new direction. Thankfully, just when the style starts to show its wear and tear, things take a noticeable turn.

Books 5-7

The Situation Worsens

The Austere Academy marks the turning point for the series, so if you can make it here, you’ll be in pretty good shape. Book five is where the ‘season two’ of Unfortunate Events begins, both literally (at least, it will, assuming that Netflix gives us another round of episodes) and figuratively. You see it a lot on television: the first year is lighter in tone and easily divided into succinct, standalone plots, while the next gets serious and starts emphasizing longer arcs and more elaborate world-building.

That’s a pretty good summation of how these installments go. Characters with notable roles throughout the remainder of the series (the Quagmires, Carmelita Spats, Esmé Squalor) are introduced, the premise for each book gets grimmer (even more child endangerment, harsher deaths, more dramatic stakes beyond just the Baudelaire fortune), and — most importantly, perhaps — the larger mysteries get introduced: the V.F.D. organization, the sugar bowl, the specifics of the fire that destroyed the Baudelaire’s home.

Sure, the outline for each novel remains the same (the orphans are shuttled to a guardian, Olaf arrives in a disguise, things go south, the orphans stop Olaf, Olaf escapes — rinse and repeat), but the greater emphasis on longer plotlines does wonders in making the repetition less noticeable, and therefore generally less of an issue. And even these elements are mostly exorcised by the time The Vile Village rolls around, which in turn establishes a second, more drastic shift in formatting by its end.

Books 8-12

The Dilemma Deepens

From The Hostile Hospital (which earns the title as my second-favorite installment, though I give The Grim Grotto the highest honor) onward, the ‘new guardian, new disguise’ bit is discarded entirely in favor of the big questions and unanswered riddles, with the Baudelaires now alongside allies in direct confrontation with Olaf and his crew. Each adventure still gets its own distinct theme and setting, of course, but the focus now is on continuing wherever the last left off.

Personally, I see this stretch as the strongest. More explicit continuity means more investment in the characters and the direction that their story is going, along with a nice heightening of the drama and intensity that is impressively mature for a middle-grade series. Despite the (rather unrelenting) somberness, however, Snicket’s general weirdness is still in full effect, and you never quite lose the underlying optimism despite the ‘it’s always darkest before dawn’ approach. It’s a very hard balance to achieve, I think, but the author pulls it off beautifully. On the one hand: a refreshingly frank examination of some very weighty themes (mortality, open-mindedness, the values and dangers of deceit and ignorance) that doesn’t enforce bleakness solely for the sake of being ‘edgy,’ but respects the intelligence of younger readers and the importance in understanding the less dichotomous, less cheery sides of life. On the other: a quirkiness that manages to be very funny very frequently without seeming out of place or pandering (“Think of the children!”) or inappropriate.

Not to mention the continually evolving and deepening sense of mystery that ties it all together. Again, Snicket is smart about juggling it: he doesn’t put off explanations or reveals so long that you stop caring about them, or build the anticipation so greatly that the actual unveiling is inevitably a let down. Yet neither does he give away his secrets too easily, each unmasking usually leading to two more, or at least not giving everything away all at once. He expects the reader to figure certain things out from the clues he’s trailed behind rather than spelling it out in a big, splashy scene. There’s plenty to pull you along from one book to the next, but not to a degree that you feel like you’re being strung along.

The Penultimate Peril is appropriately named as the final setup. It manages to bring just about every other installment into its folds and tie them all together in a rather tidy manner, creating a satisfying sense of unity from a dozen different yarns. It does so cleverly (mainly through a healthy dose of meta), thoughtfully, and so assuredly that you feel certain that the finale is going to bring it all home. “Finally,” you say to yourself. “A mystery writer who didn’t just make it all up as he went, only to blow it at the last minute because he had to pull something out of his ass!”

If you’ve read these, you know where this is heading. So let’s turn, last but not least, to…

Book 13

The End

The thirteenth book gets its own section for two reasons. One: it is the culmination of so many previous stories that reaching it is something of an achievement, even if none of those stories were particularly long.

Two: it’s a mess.

Surprise, surprise. When hasn’t the last novel of a popular children’s series not been controversial for one reason or another? The End is such mostly for the same reason that Lost (see ‘Mystery Writer Who Made It All Up as He Went, Only to Blow It at the Last Minute Because He Had to Pull Something Out of His Ass’ above) is.

All of those fascinating mysteries? The bizarre questions? The tantalizing half-reveals? You’d better like them just as they are, because that’s all you’re getting. Suckers.

Well, not entirely. You do get some explanations, but they’re mostly for the more minor enigmas. The biggest ones? Snicket pretty much leaves it up to you to come up with something. This works with some — as he’s scattered enough pieces throughout the many books for you to piece together a fairly clear whole yourself — and not so much with others, which are just left to keep you up at four in the morning, when you could be doing more productive things, like sleeping, because it’s a Wednesday and you have to get up for work in three hours.

How irritating.

And, you know what? It totally works for me.

If you hated The End, I understand. Truly. It’s frustrating having so many things left unclear. To me, though, it’s entirely fitting. Snicket actually makes a point of driving this concept home throughout the book: our lives are a miniscule fraction of an endlessly shifting and complex system (whether that system is ‘human society’ or ‘the entirety of space and time’) that no one person can never fully comprehend. The best that we can do is realize the limitations of our perspective and make do with the niche that we’ve carved for ourselves.

It almost — almost — feels like a cop-out. Snicket spends much (perhaps too much) of his last story justifying his ending while actually, you know, revealing said ending, to the point where you can’t help but believe that, yes, we are once again dealing with a writer who couldn’t be bothered to think ahead and actually find adequate time to wrap up his creation properly.

But.

I like it. I really do. Because it’s symbolic, dang it. A Series of Unfortunate Events was never truly about worldwide conspiracies and the years of history behind warring secret societies. It was about three children who were thrown into some terrible situations and had to survive through their wits and their love for one another. The rest of it — V.F.D., the sugar bowl, the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of the fire and the many like it — was thrust upon them when it was never meant to be. It is and was always a secondary backdrop on which to show what happens when three scared but very brave children are thrown without rhyme or reason into the great, wide world and all of its cruelty and forced to fend for themselves. So we, the readers, are given a much more realistic conclusion to match the perspective of our protagonists: the closing of one door, the opening of another, and no more than the edges of a great many other, larger things. Because fiction may be able to give us helpful guides and summaries and exposition for every little thing, have it fit in a perfectly cognizant and understandable whole, and wrap it all up with a definitive outcome, but reality isn’t like that at all. Reality is vast and unknowable. Nothing truly ends. People come and go, and we get to see and understand a very small portion of their pasts, their presents, and their futures. That’s what we have to accept, because that’s just how life works.

So the Baudelaires journey ends, but not really. Snicket actually has the sheer cheek to leave us on a very open note (not quite a cliffhanger, perhaps, but pretty close) and the last-minute reveal that the one mystery — quite literally the first one that the series introduced, in fact — we thought had long been figured out is, surprise, still very much unresolved.

And it works. Because it ultimately upholds the promise that the opening sentence of the opening chapter of the opening novel gave us: that we were in for an unfortunate series of events with no real happy ending. Happy endings mean closure, don’t they? And closure isn’t something truly attainable in the real world, is it? So the Baudelaires don’t get those things, and neither do we. It’s a gutsy way to leave things, but I give Snicket plaudits for doing it, largely because, looking back, it feels like the natural culmination of not just the storyline, but the entire point of the books as well. And that fact — that this conclusion seems to be one that the author had more or less planned for and saw through to its completion, despite knowing that its unorthodoxy was going to rile some feathers — makes it less a disaster than it might otherwise have been. It’s not satisfying in the traditional sense, but that’s the point.

Gosh, I love it.

Being a General Retrospective of Books One Through Thirteen, Prior to a Conclusive Evaluation

To summarize, then:

The Bad

Ending aside, of course. The repetitive nature of the series, especially at its start, is tedious and seems to limit the storytelling possibilities. It’s less of a problem during the latter half, but heavier continuity brings its own set of problems: details start to slip through the cracks, some blatant contradictions pop up, and the motives of some of the characters become rather thin when stretched over so many books, if not outright difficult to believe. (My go-to method for hand-waving these is to chalk them up to either an unreliable narrator and/or the ‘dark fairytale’ style that the series subtly draws upon. Everyone acts ridiculous in fairytales, right?) You may find Snicket’s writing style trying too hard to be witty, or too intrusive, or just outright obnoxious. You may have your suspension of belief too frequently threatened, as the narrative does have a tendency to veer from a more quiet realism to a more blatantly wacky fantasy, then back again, within the course of one chapter.

All valid criticisms, certainly. It certainly isn’t a perfect series.

But.

The Good

But it’s also so full of personality and life that I fully forgive the rough edges, and I hope that you can, too. It’s smart. It’s profound. It’s hilarious. It’s rather disturbing. It’s so many things beyond what we like to dismiss as ‘kiddie fiction.’

Snicket (the pen name, I should add, for one Daniel Handler) isn’t an omniscient narrator passively describing events — he’s a character all his own who exists within the world of the story itself, slipping in his own thoughts and personality so frequently that he just about smashes the fourth wall to bits. He’ll fill up several pages with uninterrupted black to simulate the darkness of an elevator shaft. He’ll abruptly end a chapter because of a dinner party that he’s attending. He’ll force you to read the same line multiple times while talking about how falling asleep while reading causes one to read the same line multiple times. He’ll include a letter to his sister to warn of danger in the middle of a paragraph and make no mention of it ever again. He’ll take an aside to describe how the Baudelaires’ situation would differ had they been stalks of celery instead of children. He’ll lampshade and foreshadow and outright discuss every trope that he uses as he uses them. If you’re into that sort of thing, it’s a joy to watch him play with the medium so casually.

But beyond the gimmick of a fun storyteller is a real brain and a definite heart. Just about every name for every single person, place, and thing is an allusion or reference to an author or obscure word. His dissection of tropes isn’t simple name-dropping but an actual examination of how they work, what they’re for, and why we use them. And, as I already mentioned, he has no qualms about looking at tough topics in a beautifully straightforward and honest way, whether it be death or the nature of evil or the merits of carpooling, and he’ll fit them into the plot in a way that isn’t ham-fisted or preachy in the slightest. Snicket doesn’t tell a weird story in a weird way just because he can. He does it because he knows that children are a lot smarter (and much more vulnerable to, and aware of, ‘adult’ fears and dangers) than we usually give them credit for, and that they can handle fiction that isn’t just escapism, but also a contemplation of narrative’s purpose, its limitations, and what it can and cannot do for us. If he can provide some guidance for dealing with helplessness and grieving, Snicket will do so gladly. because he knows that the youngest of us are just as likely to struggle with these situations as the oldest. He’ll just do it while also filling an entire page with nothing but the word ‘very’ to really drive the point home.

It’s a love-letter to the art of storytelling, really. And it’s wonderful.

Being a Final (and Mercifully Brief) Summary of Those Works Deemed Important, but Ultimately Secondary, to the Baudelaire Legacy

Finally (this got so long, I’m so sorry), give me just a moment more to cover the two supplementary works that directly tie into the main series. As I mentioned at the start, the All the Wrong Questions tetralogy isn’t included here, as its impact on your understanding of these books is mostly minor. Because it focuses on Snicket and his time with V.F.D. as a young man, it’s a nice addition for learning a bit more about the bigger picture of his world (you know, the thing that The End makes a point of not addressing), but not about the Baudelaires. And they’re the crux of the story.

So, we just have these works. Both are very short and very quick reads. Will they bestow fantastic, last-minute insight into the main installments? No. But they do clear up a few (mostly smaller) loose ends and help sketch a better understanding of the context behind the books’ events (and even a bit beyond them), if not the events themselves. And, naturally, they manage to throw in a few additional curiosities for good measure.

Lemony Snicket: The Unauthorized Autobiography

★★★★☆

It’s about as straightforward of an autobiography as you would expect. The patchwork nature of the book (a collection of various newspaper articles, scribbled letters, coded messages, photographs, and more) helps piece together some of the backstory of Snicket and the older V.F.D. members as they were before, during, and after the story of the Baudelaires. None of this information is ‘new,’ perhaps, but it helps straighten out bits of the worldbuilding that we’ve only had vague hints or guesses at previous to this, such as why Mr. Poe disappeared during the latter half of the main series and what Kit was up to prior to her appearance at the end of The Grim Grotto.

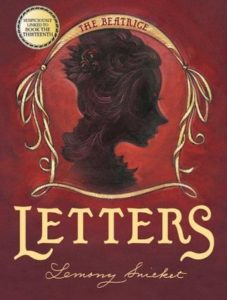

The Beatrice Letters

★★★★☆

Something of a novelty, this is a collection of thirteen letters between Snicket and Beatrice — a woman you learn of early in the main series and discover more about as it progresses. It does two things:

- It reveals a bit more of Snicket and Beatrice’s past, set long before the main books.

- It reveals a bit more of what has happened to the Baudelaires since The End.

As such, despite its length, The Beatrice Letters is a sort-of-important piece of the canon, because it contains the latest chronological pieces of the story. Unsurprisingly, this would-be epilogue isn’t any less vague or unclear. If anything, it leaves the status of things even more open than they were before. Whether this is a good or a bad thing is up to whether or not you liked how things were left there. As you might guess, it seems to me a fitting follow-up. While I liked the feeling of the primary ending, this one acts as a nice check-in to assure you that the characters are still around (hopefully, anyway) and still abroad in their big and mysterious world. Of course, it adds yet another unanswered question to the pile of holes that Snicket hasn’t deigned to fill in yet (and sort of ruins the sliver of closure that came with the previous finale), but that’s his thing, and I’m not a bit surprised he thought it prudent to pull it one final time here.

Beyond that, the additional insight into Snicket and Beatrice’s relationship is nice for the sake of characterization, but doesn’t add anything new to what we were already able to work out from the earlier books. The whole thing comes in a lovely package, though, with a portfolio and poster and punch-out letters that can be used to spell out a code. Gimmicky? Maybe. But it sits within the conceit of the series nicely. It may not be a fourteenth book with a real, true, definite ending, but it’s probably the closest thing to one that we’re going to get, and I’m okay with that.

Being the Conclusive Grading for the Tale of the Baudelaire Orphans as a Collective Work of Fiction Both Lengthy and Unpleasant

Here we are, at long last. I appreciate your staying with me for so long. If you read all of this, I’m truly grateful. If you didn’t, just pretend that you did. How am I to know that you’re lying? I hope the falsehood weighs on you tonight, however. How can you sleep, knowing how untrustworthy you are?

Anyway, if it isn’t obvious by this point (and I pray that it is, or I’ve failed spectacularly), permit me to summarize: These books are very good, and I love them dearly. I have for a long time, and I think that I always will. Unlike some childhood favorites, they’ve stood the test of time — in fact, I think that I appreciate them more now, given how many references and clever writing tricks didn’t register with me when I was younger. If the many caveats surrounding the final book don’t put you off, I definitely recommend them. They’ll fly by, I promise.

Five stars out of five.

There you have it. A comprehensive guide to A Series of Unfortunate Events. Take from it what you will.

Tune in a week or two from now, then, for another probably-too-long review of the first season of the television series. I’m excited. Can you tell?

In the meantime, I leave you with a quote from The End. Only fitting, given that I started this monster of a review with one from The Bad Beginning. I think it summarizes just how insightful (and, well, unfortunate) this series can be:

“It is almost as if happiness is an acquired taste, like coconut cordial or ceviche, to which you can eventually become accustomed, but despair is something surprising each time you encounter it.”

Savannah @ Playing in the Pages

Holy cow, you are not kidding when you say this review is “comprehensive.” There isn’t a single angle you missed in figuring out how to discuss this series – one that is dear to my heart, too, for exactly those same kind of Scholastic Book Fair reasons – and you did so wonderfully! It was only in a recent conversation with my teenage brother that it was revealed he had never read the original series, so I think a tag-team reading marathon is in order for me soon. 🙂 Great review!

Monteverdi

Nostalgia can certainly be a double-edged sword, should you revisit a book and find out that it isn’t quite as great as you remembered it being. It’s good to see this series avoiding that. Watching the Netflix series has me wanting to reread them already.

Kate Copeseeley

You know what’s weird? Before I logged in, it asked me what I would rate the book, but then I logged in and that option is gone. Ah well.

I completely agree. I read this series in college, but that didn’t stop me from loving it to pieces. And now my kids are old enough to read it and I’m sooo excited for them to get that chance (and watch the series on Netflix, ngl)

Nice job on summing up the whole series. There were books listed that I was unaware of!

Monteverdi

Thank you, Kate. I sat down and watched the new season in one go over the weekend with a friend of mine, and we both agreed that it did a very good job with the source material. It isn’t perfect — but no adaptation ever can be, especially if it’s a treasured one.

And you should certainly consider the side books! They’re all very easy to get through and are fun additions.

Lizzy

I’m so excited to read this review! I read the first book and only the first book years ago and recently picked up the first 4 to start on again. I’m definitely planning to read the entire series, probably in a weekend or two. Awesome post.

Carina Olsen

Ohh, lovely review Monteverdi 😀 So glad you loved these books so much. <3 Yesss. I haven't seen the netflix show yet, but gosh, I loved that movie from years ago 🙂 SO GOOD. I haven't read the books yet, but I am so so curious about them. They seem amazing. You make me more excited about them 🙂

TV Review: A Series of Unfortunate Events — Season 1 | Cuddlebuggery Book Blog

[…] Is this a good or a bad thing? I can’t decide. It probably boils down to how well you liked the conclusion of the original series, and whether ‘the point’ that Snicket tries to make with it was fitting or not. (I won’t go into all of that again, but you can find my thoughts on the matter near the bottom of my review here.) […]